The State Revenue Offices of Australia are actively increasing enforcement in relation to payroll tax liabilities. In this context, tax rules do not neatly apply to employment and contractor relationships. This article explores whether simply characterising workers as a contractor is enough for a business to avoid non-compliance with tax laws that are designed to apply to employers. The task of determining whether these laws apply to these new business models is complicated by the nature of both the provisions and the case law in this area. The article focuses on the liability these businesses have to superannuation and pay-as-you-go withholding as well as, to a lesser extent, Victorian payroll tax. Practitioners should be conscious of general employment law and other related purposes. The contractual relationships and physical activity of these businesses are key to applying the relevant rules.

Business models can often fall foul of existing tax laws. This article examines how an entity running a service business, that engages people who willing perform services for customers, may have to reconsider the tax implications that may arise from their business model. Indeed, even where no employment relationship exists, liability to taxes such as payroll tax can still be caught by contractor provisions, see the Victorian State Revenue Office (SRO) tax ruling PTA-033 (Contractor Provisions).

One of the key areas that practitioners should consider is the often-fraught characterisation of an employee as a contractor by entities running a service business. The mischief from the ATO’s point of view is the avoidance of an employer’s obligation relating to superannuation guarantee (SG) and pay-as-you-go (PAYG) withholding. However, not only is this characterisation made more difficult by elements of complexity due to the differing definitions used for tax and for superannuation purposes (as well as for payroll tax), but there is also a raft of other consequences that may arise in the event of incorrect characterisation.

For instance, the entitlements to annual leave, sick leave, long service leave and other benefits as well as the entity running the service business and their liability to work cover and payroll tax (as previously mentioned) in various States to a greater or lesser extent while driven by this characterisation cannot be determined purely by reference to it. A civil penalty may also arise where the service providers are entitled to minimum benefits under an award (indeed this may result in criminal sanction, for instance, under the mandate of the Victorian Wage Inspectorate).

For present purposes, the employee/contractor characterisation relevant to PAYG and superannuation obligations will form a focus of this article.

Payroll Tax

The SRO in Victoria (and indeed the Office of State Revenue in NSW as well as other State authorities) is enforcing Division 7 of Part 3 of the Payroll Tax Act 2007 (Vic). These provisions deem contractor payments to be taxable wages and are known as Contractor Provisions.

The SRO is enforcing Contractor Provisions and applying them to medical centres as evidenced by two seismic cases, one in Victoria and one in New South Wales.1 While this is especially concerning for businesses that run medical centres (and similar businesses) it is how these provisions apply to the broader subset of entities running service businesses in the economy and how they apply in conjunction with other laws at both a Federal and State level to impose liability that will have a more profound impact upon a practitioner and how they advise these types of businesses.

While payroll tax liability may be given the most media attention at the moment, practitioners should be conscious that often the greatest commercial consequence of getting this wrong will come from PAYG and SG liabilities.

Tax and superannuation

Whether an individual is a contractor or employee is a common law consideration made predominately by reference to the contract between the parties.2 However, this characterisation is complicated by the legislative context and modification of the rules for both PAYG withholding and superannuation.

The general principles will guide a practitioner as to whether a contractor for an entity running a service business is an employee at common law. However, the legislative framework puts this characterisation in its context and may extend or modify the common law concept. Accordingly, the legislative framework is a necessary element for any analysis on this point. A potential complication to this analysis is that the legislative provisions dealing with the liability to PAYG withholding and SG use different definitions and impose liability in different circumstances.

The legislative framework for liability to PAYG withholding is encapsulated by the operative provision s 12-35 of Sch 1 to the Taxation Administration Act 1953 (Cth) (TAA). This provision states:

“An entity must withhold an amount from salary, wages, commission, bonuses or allowances it pays to an individual as an employee (whether of that or another entity).”

Several key concepts arise when examining this provision. The most critical one is the use of the word “employee”. This word, for the purposes of schedule 1 of the TAA, is not defined and therefore should take on its ordinary meaning within this context. The other less obvious point to be gleaned from the consideration of this text is that the liability to withhold arises where an amount is paid to an individual as an “employee” by an entity even where the individual is an employee of a completely different entity. This is important because, even where a business is not the employer of an individual, say, because they are performing a task for another party entirely, it may still be liable for PAYG if it is the one making payment to that individual for the services they perform.

In other words, when practitioners consider this provision’s elements, the payment from an entity and whether the payment was in relation to an employment activity (irrespective of whether the person performing services for the customer is working under a contract with a business or another third party) is important when deciding which entity for a given arrangement is liable to PAYG withholding. Note that the term “entity” is defined in s 8AAZA TAA to mean a company, partnership, person in a particular capacity of trustee, body politic, corporation sole or any other person.

The practitioner when examining an entity and their service business should note that this is not the only provision that imposes a liability on an entity to withhold an amount under the TAA. Related withholding rules that a practitioner should consider along with the PAYG withholding rules for employees (amongst others) are the following:

- payments to company directors;

- payments to officeholders;

- payment under labour hire arrangements; and

- payments under the personal service income (PSI) rules.

The legislative provision used to define when an entity will be an employee and when an entity will be an employer to impose a liability for SG purposes is s 12 of the Superannuation Guarantee (Administration) Act 1992 (Cth) (SGAA). This provision (similarly to the TAA for PAYG withholding) relies on the ordinary meaning of the words “employee” and “employer” to define when an entity will be liable to pay SG (provided other conditions are also met). The difference is that this provision both extends this ordinary meaning and clarifies for the avoidance of doubt the status of certain people. The important re-characterisation for the purposes of this article is the following term from s 12:

“If a person works under a contract that is wholly or principally for the labour of the person, the person is an employee of the other party to the contract.”

The key thing to draw from this provision is that, where an individual works under a contract that is wholly or principally for the labour of the person, the person will be deemed to be an employee for superannuation purposes even if they are not an employee at common law. Unlike the PAYG rules, this rule arguably only applies to the two parties to the contractual relationship.

When one examines both legislative provisions (and those for payroll tax) together, the difficulty for practitioners becomes clear. The reconciliation of an entity that undertakes a service business and their obligations for these related but different liabilities can be confusing and the consequences arising from these characterisations are in many cases not intuitive. This is notwithstanding the fact that they may have a very real (and potentially adverse) tax and/or superannuation impact.

One consequence of note arises because both SG and PAYG are subject to the director penalty notice (DPN) regime. This means that these liabilities (for SG and PAYG) resulting from an incorrect application of the law not only can result in liability for the entity running the service business but can also consequently result in parallel liabilities falling on their directors.

Ordinary meaning of “employee”

The ordinary meaning of the word “employee” has been refined through a great body of case law, both in Australia and overseas. The distinction between an employee and a contractor can be encapsulated by the nature of the relationship these parties have to the entity engaging them and two opposing characterisations that describe these types of relationships.

The first principle is that an employment relationship is described as a master and servant type relationship where the parties enter a contract of services. In other words, the employee serves the employer. The second opposed characterisation is that a contracting relationship is a contract for service. So basically, two businesses enter a contractual arrangement to achieve a given result. The issue is that no definitive condition or factor will lead to a characterisation of any given relationship as either one of employment or one of contracting, each case will need to be considered based on relevant factors and a decision made accordingly.

This means that the contract (or contracts) between individuals providing something to an entity running a service business should firstly be analysed to determine whether they could be characterised as applying to an “employee” at common law. The factors that indicate whether an activity may be categorised as that of an “employee” activity are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Employee activities

| Factor # | Factor | Indication may lead to | |

| Employee Characterisation | Contractor Characterisation | ||

| 1 | Control of the worker in terms of how, when and where work will be performed. | Entity running business controls worker. | Worker controls themselves. |

| 2 | Integration of the worker into the business and whether they are held out as a representative of the business. | Representative and worker provides services to further entity running business. | Not a representative and provides services to further worker's own business. |

| 3 | Mode of remuneration and whether worker is paid to achieve a result often for a fixed fee. | Paid hourly or for time worked. | Paid for a result often for a fixed fee. |

| 4 | Ability to subcontract or delegate work of the business. | Cannot subcontract or delegate. | Can subcontract or delegate. |

| 5 | Provision of tools and equipment by either the entity running the business or the worker. | Worker does not provide tools or equipment. | Worker does provide tools or equipment. |

| 6 | Risk of the business being borne by the worker or the entity running the business. | Risk of business borne by entity running business. | Risk of business shared with worker. |

| 7 | Goodwill and whether the worker generates this asset or not. | Goodwill generated by worker accrues to the entity running the business. | Goodwill generated accrues to the worker's business. |

It is important to note that no single factor (summarised and described in Table 1) will be conclusive when determining whether the entity is an employee or a contractor at general law.3 The High Court has held, in respect of the characterisation as employee or contractor that it is the contractual relationship between the parties and the specific terms and conditions under which the work is performed that are most importance where a valid and binding contract is in place (and that this aspect of the arrangement is not in dispute).4 The other important thing to draw out from the case law is that all the indica overlap and interrelate and cannot be used as a checklist. A relationship may have overwhelming factors that indicate it is a contracting relationship and yet, due to a lone factor given more weight in the circumstance, be one of employment.

The obligation to pay SG is extended to contractors where the contract is either entirely for the labour of a person or this is the main reason for the contract. The terms of a contract, as well as all the facts surrounding a particular relationship, are important when determining whether the contract with a person satisfies this extended definition.

This means that, even if an entity running a service business succeeds when determining that an individual is not an employee, they may nevertheless be liable to pay superannuation if the contract is principally for labour. The assessment of these relationships happens in every period in which SG or PAYG can arise.

Consequences for service businesses

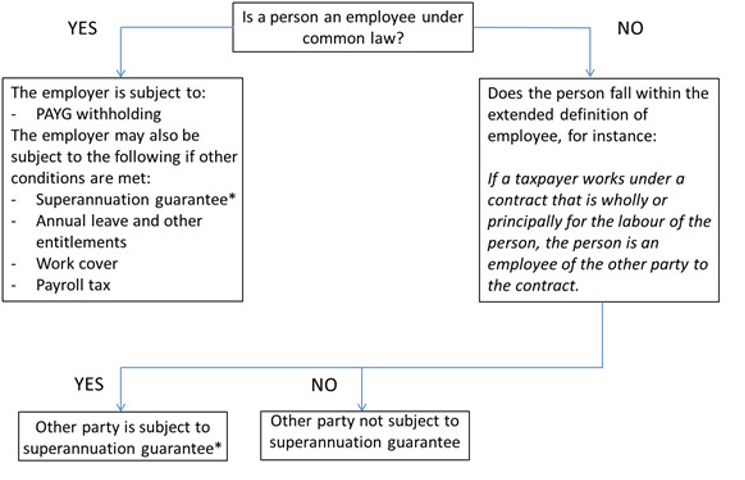

The consequences of being an employee will depend on whether an individual is characterised under common law as an “employee” or under the extended definition under the SGAA. Diagram 1 gives an overview of the consequences of this characterisation.

Diagram 1. Liability to Employment Taxes Decision Tree

The consequences for a contracting party that arise for a common law employee are far-reaching. The difficulty in deciding whether an individual is an employee at common law remains. The added difficulty of determining whether a contract is wholly or principally for labour may also cause confusion or additional complexity.

The contract is critical

The contractual arrangement of the parties involved are key. An entity running a service business cannot simply require that contracts for service are signed between themselves and another entity with an Australian business number (ABN). The direction of the payment of the funds is also an imperative consideration when determining whether a liability is imposed for PAYG withholding.

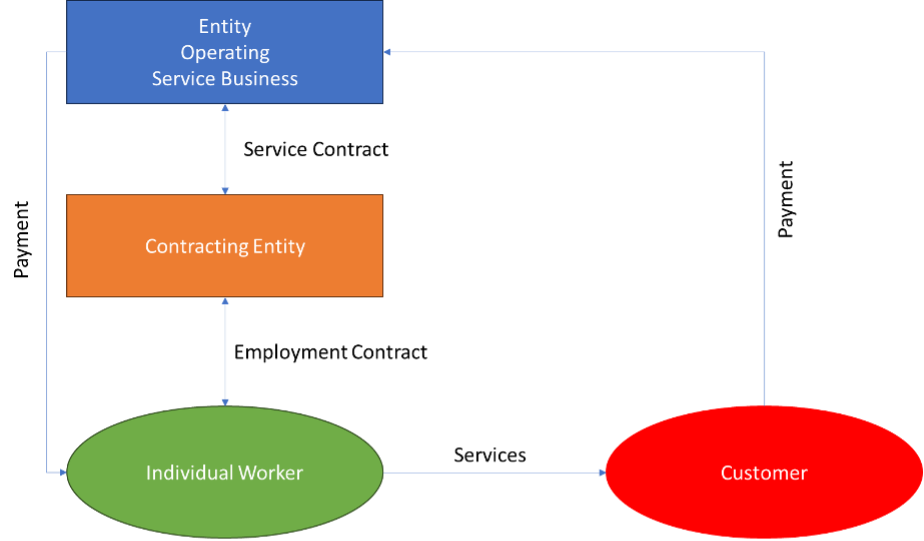

This means that, when an entity running a service business contracts with another entity (that may or may not be a related party of the individual providing services under the contract) where the payment goes directly to the individual, the business making the payment may still be liable for PAYG withholding even though the individual is not an employee of the entity undertaking the service business. To illustrate this point, see Diagram 2.

Diagram 2. Relationship to individual performing service and Consumer

The liability to SG in Diagram 2 should be with the Contracting Entity but can also be with the Entity Operating Service Business if the Service Contract between those two parties is wholly or principally for the Individual Worker’s labour.

However, for PAYG withholding purposes, because the Entity Operating Service Business is making the payment to the Individual Worker, it is that entity potentially liable to this obligation. To further illustrate when liability for SG arises, Diagram 2 may assist.

When a practitioner considers how the structure of an arrangement may cause incorrect characterisation or an incorrect assessment as to who is liable for respective taxes, a thorough and clear understanding of this issue is a priority. The interplay of the contractual arrangements between the parties and exactly what is being exchanged is critical.

The added complications are the other “entity specific” tax rules that may arise on creating a structure for a particular arrangement. Compounding this difficulty, the other tax rules that should also be considered in consultation with both “entity specific” rules and these liabilities to withhold PAYG and pay SG are the PSI rules under Pt 2-42 of the Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth). These rules have their own results test and other tests (such as the 80% rule) but is ultimately a specific anti-avoidance rule for the alienation of assessable income rather than enacted for the purpose of imposing employment taxes.

Businesses – fictional case study

Rick James is a management consultant. He specialises in organisational change and crisis management. Rick has been in negotiations with an entity running a service business (Service Entity). Rather than hire Rick as an employee, the Service Entity would rather engage him as a contractor. The Service Entity and Rick are, however, concerned about the potentially significant on-costs of the arrangement (specifically PAYG withholding and SG). They understand that the arrangement may be different legally to how they describe it using common business language. The contract and other particulars of the arrangement between the parties is first analysed with reference to the relevant factors discussed in various case law judgments. The Service Entity would rather contract with an entity that runs an IT business (IT Entity) that in turn contracts with Rick James. A summary of the analysis is set out in Table 2.

Table 2. Factors in deciding employee v contractor characterisation

| Factor # | Factor | Indication may lead to | |

| Employee Characterisation | Contractor Characterisation | ||

| 1 | Control of the worker in terms of how, when and where work will be performed. | Worker controls themselves. | |

| 2 | Integration of the worker into the business and whether they are held out as a representative of the business. | Representative and worker provides services to further entity running business. | |

| 3 | Mode of remuneration and whether worker is paid to achieve a result often for a fixed fee. | Paid for a result often for a fixed fee. | |

| 4 | Ability to subcontract or delegate work of the business. | Cannot subcontract or delegate. | |

| 5 | Provision of tools and equipment by either the entity running the business or the worker. | Worker does not provide tools or equipment. | |

| 6 | Risk of the business being borne by the worker or the entity running the business. | Risk of business shared with worker. | |

| 7 | Goodwill and whether the worker generates this asset or not. | Goodwill generated accrues to the worker's business. | |

Rick opens a bank account in his name (the bank account is where deposits from the Service Entity will be forwarded). Rick’s legal advice indicates that, on balance, even though, when looking at the factors in Table 2, he satisfies more factors that would lead to a contractor characterisation, when he executes the contract, he is likely to have entered an employment relationship with the Service Entity at common law. This is due to the body of case law and relevant weighting of the factors specific to his individual case. The parties to the contract are Rick, the Service Entity, and the IT Entity (with Rick performing the relevant services).

The Service Entity is concerned as it will make payments to Rick James, it may incur PAYG withholding, notwithstanding the fact that the relevant employment relationship, were it to exist, is between Rick and the IT business. It is specifically concerned with s 12-35 of Sch 1, which states:

“An entity must withhold an amount from salary, wages, commission, bonuses or allowances it pays to an individual as an employee (whether of that or another entity).” (emphasis added)

When considering liability to SG, the Service Entity is even more concerned about its liability to superannuation for Rick James. It reviews s 12(3), which states:

“If a person works under a contract that is wholly or principally for the labour of the person, the person is an employee of the other party to the contract.”

In Rick’s case, he satisfies s 12(3) because:

- he is a person working under a contract; and

- the contract is principally for his labour.

Rick’s legal advice also points out that arrangements to avoid SG can also expose parties to criminal liability, see s 30 SGAA, which states:

“If:

(a) an employer makes an arrangement; and

(b) as a result of the arrangement the employer’s superannuation guarantee shortfall for a quarter is reduced; and

(c) in the Commissioner’s opinion the arrangement was made solely or principally for the purpose of avoiding payment of superannuation guarantee charge otherwise than in accordance with this Act;

the employer is liable to pay for the quarter an amount of superannuation guarantee charge equal to the amount that, in the Commissioner’s opinion, the employer would have been liable to pay if the arrangement had not been made.”

The other consideration is whether the laws of agency will change the operation of the SGAA or PAYG rules. This is a valid consideration. However, these rules are formed as integrity measures to make sure that employee obligations are met even if the employer does not make payment, so this would be unlikely.

Conclusion

The above scenario is one way that an employment relationship can arise. The more direct and simpler way that an entity running a service business may be subject to these rules is if its relationships with providers of services are characterised as employment rather than as contractor relationships in their own right.

The importance of understanding how a relationship will be characterised for the purposes of the income tax and superannuation laws should not be ignored by practitioners. PAYG withholding and SG represent significant costs of doing business in Australia. The structuring of contractual arrangements, respective legislative frameworks that operate in this area and also the flow of funds between parties when providing advice pertaining to these employer obligations are all critical.

The payment of remuneration to an entity and whether this is for the labour of an individual are key aspects that may trigger liability. Consideration of a worker’s status as either employee or contractor is of particular importance now in an environment where the ATO and SRO is stepping up compliance activity.

Danaher Moulton can assist with complex taxation matters. If you need any assistance with these matters, contact Bill Mavropoulos, Lee Patouras or Peter Saunders.

1 Thomas and Naaz Pty Ltd v Chief Commissioner of State Revenue [2021] NSWCATAD 259; Commissioner of State Revenue (Vic) v The Optical Superstore Pty Ltd [2019] VSCA 197.

2 WorkPac Pty Ltd v Rossato [2021] HCA 23; Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1.

3 Hollis v Vabu Pty Ltd [2001] HCA 44.

4 Construction, Forestry, Maritime, Mining and Energy Union v Personnel Contracting Pty Ltd [2022] HCA 1; ZG Operations Australia Pty Ltd v Jamsek [2022] HCA 2.